Big buildings consume enormous amounts of energy, but they are also one of the best ways to slash greenhouse gas emissions, slash energy costs for owners and help decarbonise the grid. If Australia’s property owners manage their time of use of energy, it could produce a template for the rest of the world to follow.

Say you’re a building owner, and you’re concerned about global heating and the climate crisis. You would certainly not be alone. To do your bit, you’d want to eliminate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from your building’s operations. If you were like most sophisticated property owners, you would start by cutting your building’s energy use through efficiency improvements.

You might put solar panels on the roof. You would probably sign a contract for “green” electricity and then electrify all your building’s plant and equipment. If you wanted your building to be certified as net zero (and why not?), you’d purchase certificates or credits to “offset” the remaining emissions that your building is responsible for.

And then, your job would be done. You could relax. Crisis averted!

But it wouldn’t be, of course.

Even if every building on Earth followed that path, the massive decarbonisation challenge would persist.

Many building owners are committed to making their buildings net zero. But only a very small proportion delve deeper and ask whether their pathways to decarbonisation could be more impactful, or if they could improve their investment returns.

Only very few building owners discover how their pathways to decarbonisation could be more impactful and how they can improve their investment returns.

Buildings (of all types) collectively use more than 50 per cent of the electricity generated in Australia, and at peak times they can demand more than 80 per cent. This is both a problem and an opportunity.

It’s a problem because most people don’t think of buildings as participants in the electricity market – they use electricity without regard for the system components.

We need to coordinate electricity demand so buildings can smooth Australia’s path to a fully decarbonised energy system

And it’s an opportunity because if demand for electricity can be mobilised and coordinated to prioritise clean and cheap renewable electricity over dirty and expensive fossil fuel generation, buildings will smooth Australia’s path to a fully decarbonised energy system.

This can also provide a template for decarbonising the built environment globally.

The nature of electricity generation has changed dramatically over the past 15 years, but the market has not kept up.

Prior to 2010, variable renewable energy (VRE) from sources such as wind and solar accounted for only a tiny fraction of 1 per cent of supply on the national electricity market (NEM).

Over the month of October 2024, VRE, including rooftop solar, has supplied 40 per cent.

In the past all the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) had to do to maintain balance in the system was monitor demand and then call on generators to ramp generation up and down to match it.

For the most part, that was done with price. If there was a need for more generation, higher bids were accepted. If the need was for less, only lower bids were accepted.

It was slightly more complicated than that but essentially since the 1950s, crude off-peak tariffs have incentivised demand from things like off-peak hot water systems, streetlights and certain industrial processes.

Now, of course, much of the generation rises and falls with the wind and the sun.

It’s not simply a matter of calling for more or less generation to meet demand – the wind and the sun simply will not obey.

What this means is that the building operator can potentially double their demand for electricity when it’s free and cut demand to almost nothing when it’s expensive

And because AEMO can’t control the demand side either, its price signalling is becoming less and less effective. The wholesale price of electricity is now typically the inverse of the wind and solar generation output: When there’s an oversupply the price crashes, and when there’s a shortage the price goes through the roof.

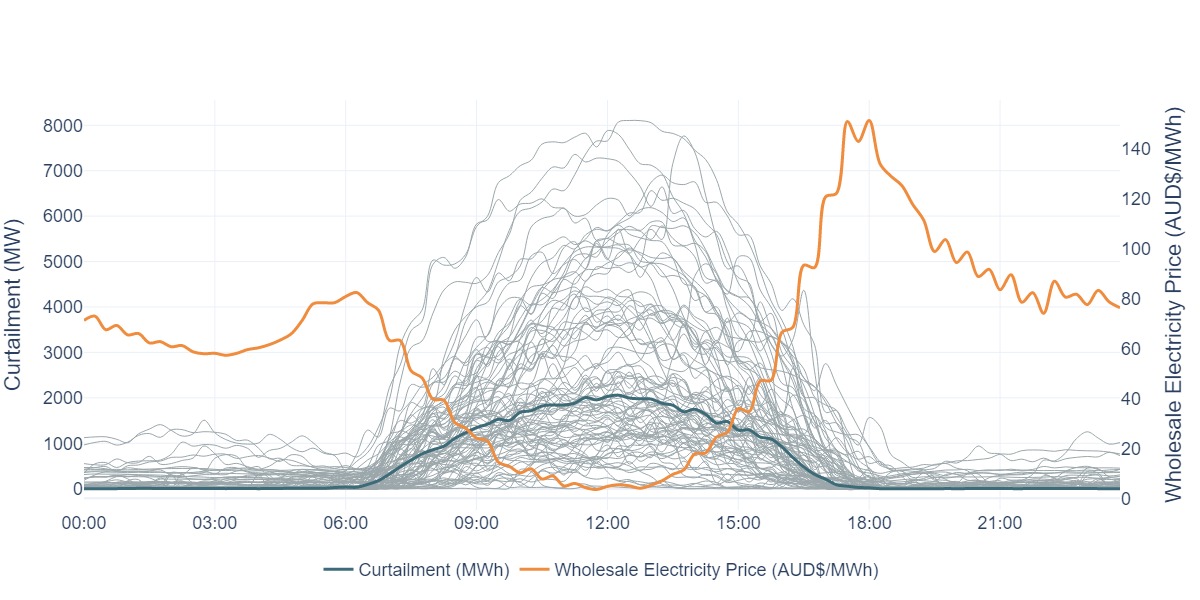

This is illustrated in the graph below for the entire 2023 calendar year, which also shows the extraordinary level of forced “curtailment”.

This is essentially the mechanism that AEMO uses in addition to price to stop unwanted electricity generation entering the market.

Curtailment, while necessary to maintain the stability of the system, is renewable energy going to waste. As can be seen in the graph, the quantity of waste is enormous.

What can buildings owners do to benefit?

Investment in battery energy storage system (BESS) is skyrocketing in Australia. Homeowners with rooftop solar panels are choosing to install batteries rather than see their excess solar go to the grid virtually for free.

At the other end of the spectrum, massive grid-scale BESSs are being installed to take advantage of the NEM’s highly predictable patterns – prices being extremely low during the day and rising sky-high during the morning and evening, as illustrated in the graph.

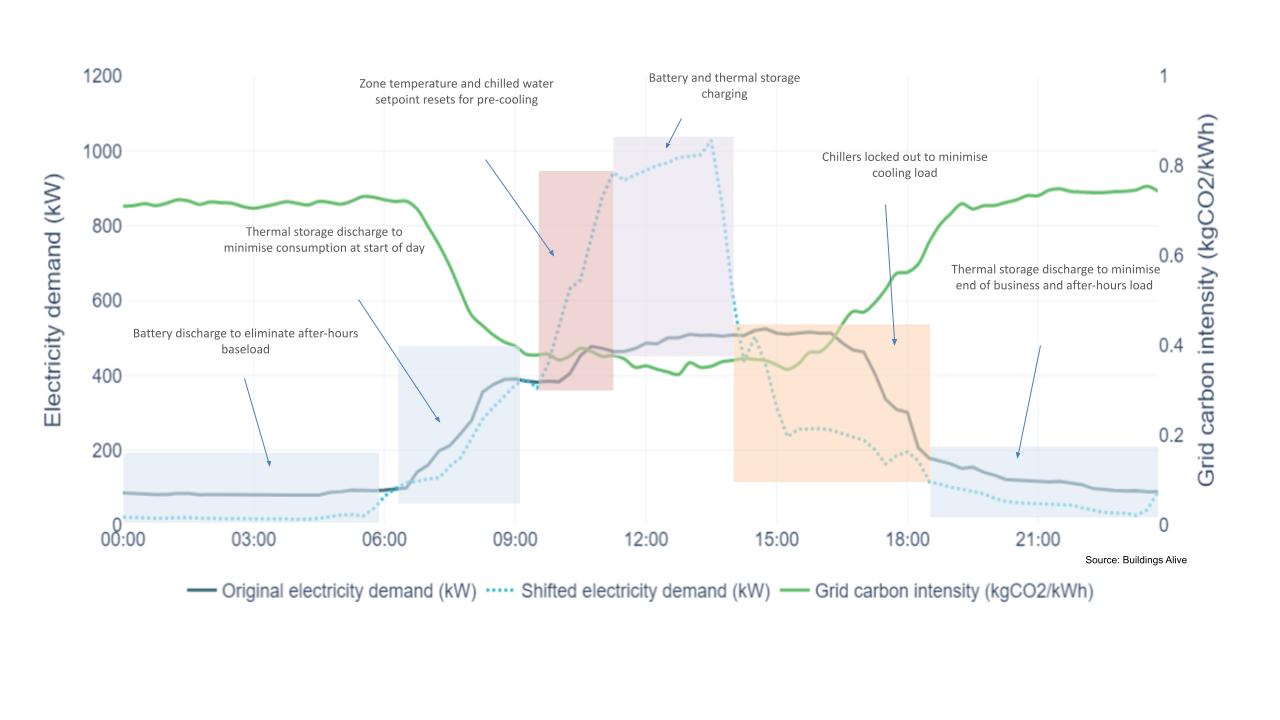

The purpose of a battery is to allow consumption of electricity to occur at times that are different to when it’s generated. We should not just think of batteries as containers storing electricity as chemical energy. A building will function as a battery if it performs work at one point in time and avoids doing the same job at another. Take the simulation below. In this illustration, the building has three energy-management assets: a thermal energy storage system (TESS), a conventional BESS, and a heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system.

The building operates as a battery, charging and discharging as follows:

- From about 10am the HVAC system works harder than it would otherwise need to (for example by providing additional cooling, heating and/or fresh air for occupants).

- Once temperatures and air quality are at their appropriate limits, the BESS is charged from the grid and the TES is heated/cooled by the building’s refrigeration plant.

- By early afternoon, refrigeration plant is locked out and a comfortable indoor environment is maintained, initially by taking advantage of temperature bands (helped by insulation and the building’s thermal envelope).

- Later in the afternoon through to early the next morning, the TES is discharged to maintain thermal comfort conditions as needed and the BESS provides other building services including lighting, ventilation and vertical transportation.

- Early the next morning most of the remaining energy in the TES and BESS is discharged to maximise the building’s capacity to draw energy from the grid again, and then the cycle is repeated.

In real life, the building’s control systems would modulate based on the real time and forecast price of electricity, the thermal conditions and requirements of building occupants, and the real time and forecast GHG emissions intensity of the electricity coming from the grid.

Unlike electricity retailers who have to assume a typical demand profile for a building and hedge their commercial risk in order to provide fixed pricing, the building owner has the opportunity to profit from the highly predictable wholesale market (as large-scale battery operators do) and hedge price risk with physical load management. What this means is that the building operator can potentially double its demand for electricity when it’s free and cut demand to almost nothing when it’s expensive.

The net impact of operating a building this way is far fewer GHG emissions because overwhelmingly the electricity that’s being consumed is coming from renewable sources. This provides the owner with investment returns that outstrip those available to conventional battery operators, and a genuinely impactful decarbonisation pathway.

Craig Roussac is co-founder and chief executive of Buildings Alive.