Alan Pears recently read the entire 900 pages that wrap up commercial building regulations. There are another 300 or so pages on plumbing regulations, about the same again on residential buildings. That’s before you get to the Australian Standards which are expensive to buy. It’s unreasonable to expect tradies, small builders, and even building surveyors, to deal with all this, he says. We need better solutions.

As we design, incentivise, regulate and construct more thermally efficient buildings, we need better design standards and regulations. We also need better trained people and more accountability. Things that didn’t matter when we had disastrous buildings now matter.

Change is happening, but it is slow and piecemeal.

The National Construction Code (NCC) is expanding to cover more than in the past.

There are more flexible requirements for efficient fixed appliances and better coverage of important issues such as the avoidance of mould and humidity that can damage building fabric. There will be separate ratings for summer and winter performances, and more.

As buildings become more efficient, and we shift to zero emission electricity, embodied emissions are beginning to dominate the lifecycle impacts of new buildings – and challenge the “bulldoze and build” culture.

BASIX in New South Wales has introduced reporting on embodied carbon emissions in building materials using a new NABERS rating tool, and the Green Building Council is emphasising this issue.

But we have a long way to go. Some of the mandated solutions for embodied carbon fail to consider fundamental physics. Others are very complicated. Suitable products may be difficult to find or expensive. Quality management and accountability measures for delivered performance often remain in the Stone Age.

The big gap between intention and performance

The big lesson I learned in my whirlwind global consultation trip when developing what is now the NABERS scheme is that there is usually a big gap between design intention and actual performance. That’s why I proposed that ABGR (Australian Building Greenhouse Rating, now NABERS) should be based on actual performance for existing buildings and a legally binding “commitment agreement” to ensure claimed performance was delivered for new buildings. This has worked. Where is a similar scheme for residential buildings?

Actual performance and commitment agreements work for commercial buildings – why not residential?

In recent preparations to give a lecture, I read through the 900 pages of the commercial building regulations, which also refer to the separate plumbing regulations of about 370 pages and about 300 on residential. In addition, there are many Australian Standards that are expensive to buy.

The Australian Building Codes Board tries hard to help, with handbooks, webinars and other resources. But it’s unreasonable to expect tradies, small builders, and even building surveyors, to deal with all this. We have to work out better solutions.

Some important issues are not yet addressed by regulations, rating tools, training products and service providers. They are also not addressed by related sectors such as real estate, regulators of owners corporations and consumer educators.

Governments have failed to empower, engage and inform key consumers to mobilise consumer pressure for improvement.

For example, how many new home buyers understand that a 6 or 7 star home is just compliant with regulations, not a fantastically high performing building that is promoted as a leading edge by a developer’s salespeople?

I don’t have space to outline many important issues, but here are a few.

Solar ovens

Many apartments are solar ovens in summer. Bans by owners corporations and poor building design make it difficult to shade balconies and glazing.

Thermal bridging is a very serious issue. Balconies, often with dark paving below, can heat up and feed heat into apartments via continuous concrete slabs (which are excellent conductors of heat).

Reflection and reradiation of heat from the balconies through windows add to the problem, as do dark blinds, often specified by designers, as they are very effective solar collectors in hot weather!

If the electricity supply fails and lifts no longer operate, residents of upper floors may be trapped, and cooked. Buildings, both new and existing, must be resilient to increasingly extreme weather and the risk of failures in energy supply. Our present rating schemes don’t adequately deal with these issues.

Bathrooms that undermine water efficient showers

The latest NCC in many cases requires bathrooms to have exhaust fans linked to the lights. This requirement, combined with “modern” shower cubicles with no doors leads people to complain about water efficient showerheads not providing enough heat.

There is some basic physics here. The heat from the showerhead warms air, which rises out of the top of the shower cubicle, drawing cold air over the legs of the occupant, and evaporatively cooling them.

People blame the water efficient showerhead, which delivers less heat, and rush to hardware stores for replacements that use much more water and heat. A “lid” on the shower cubicle (e.g. the “showerdome” advocated by energy assessor Tim Forcey) can block this airflow. A door on the cubicle also helps. A delay in the operation of the exhaust fan until people have time to dry off, instead of being evaporatively cooled as they step out of the shower, is another solution.

Building ratings that focus on annual energy and emissions, not peak demand

The NABERS rating system for commercial buildings is a world leader in requiring evidence of demonstrated performance after a building is completed and occupied.

We need something similar for residential buildings, that can be linked to people’s actual energy bills. The Passivhaus model requires a much more thorough approach and includes measures such as blower door tests for air leakage, but we need more.

A weakness of NABERS, as well as residential ratings, is that it does not address peak energy demand. This is increasingly important as we move to an energy system with more variable energy sources and prices, and global heating makes weather more volatile and extreme.

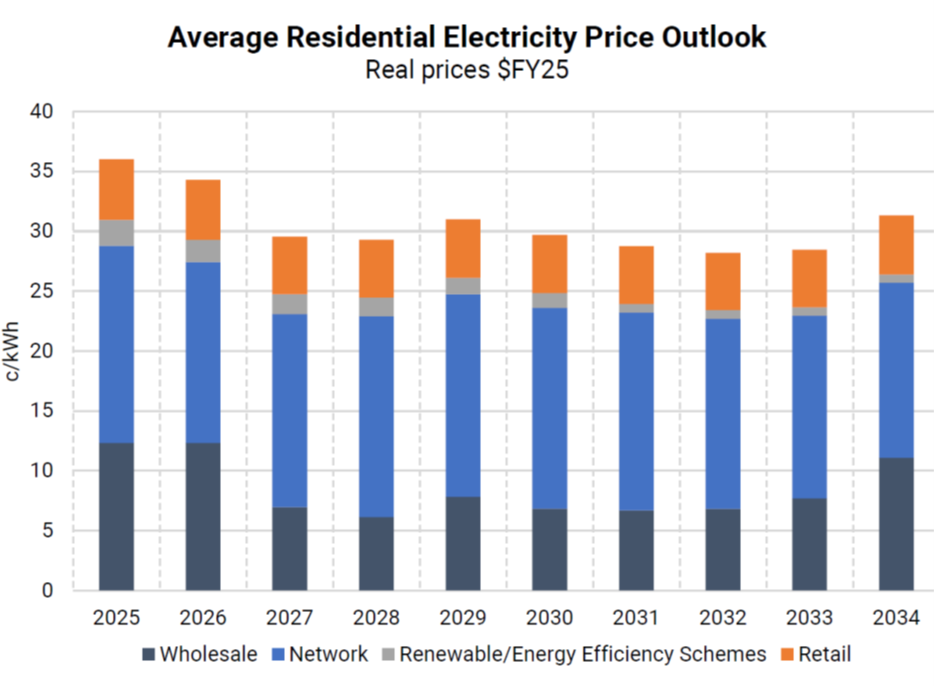

High peak demand drives dependence on reliable energy supply and more power line capacity in extreme hot and cold weather. This is fully utilised only occasionally, so capital costs are high relative to operating costs, and this flows through to high fixed charges on energy bills. Already electricity network charges dominate overall energy bills, as shown by AEMC’s latest report (see below) and can’t be avoided by most retail consumers that remain connected to the grid, no matter how efficient they are.

High NABERS rating no indication of electricity consumption

I recently analysed the correlation between peak electricity demand and annual electricity consumption of a sample of commercial buildings provided by building analysts Buildings Alive.

This confirmed that there was a very weak relationship between electricity consumption and peak demand. So it’s possible to design a high NABERS rating building that also has high peak demand. This means the building needs a larger capacity and more expensive heating and cooling equipment, and it places a higher burden on the electricity supply system in extreme weather.

I don’t want to undermine the value of the NABERS approach, as it has delivered remarkable energy, carbon, financial and comfort benefits. But we need an extra indicator, and related regulations and incentives, to focus building and HVAC designers on minimising demand at times when the supply system may be stressed and/or variable renewable energy sources may be limited. NABERS has already introduced a supplementary renewable energy index, so this provides a precedent.

We need to design new buildings, particularly apartments, to work, or to be easily adapted to work, in our changing and increasingly more extreme climate, given their long lives and our ageing population.

We have already seen some “green” apartment buildings designed to avoid the need for cooling, to face summer problems. Some residents don’t open windows, as assumed in rating tools, because of noise or security concerns. Factors such as thermal bridging are not adequately addressed by building rating tools.

The emergence of very large apartment buildings over the past few decades has created a challenging situation for their residents and unit owners.

Gaining a consensus in an owner’s corporation to update rules and fund improvements can be a nightmare. For individual occupants, bans on drying clothes on balconies or installing cooling equipment or shading that requires approval for impacts on the building fabric can be difficult or impossible. Major reform of owner corporations is needed.

Few people realise that drying clothes indoors releases a lot of water vapour that can contribute to mould and damage to building materials. Indoor plants, aquariums, high flow rate showers, cooking and even breathing release water vapour that can build up to problematic levels. Many apartments have limited crossflow and natural ventilation. Well designed, properly installed and managed energy recovery ventilation is becoming increasingly important.

We are just beginning to realise that changing climate and improving building thermal performance means that issues we didn’t think about in the past are emerging challenges.