Alan Pears has been following the challenges of electrification for many years. As a member of a small owners’ corporation, he has a few observations about how apartments can make the big switch.

In this article, he tackles the issues that often come with electrifying smaller apartments and deals with issues experienced by bigger apartment towers, such as flagged in the article by Carolin Wenzel last week about how hard it is to electrify her apartment, which is in one of 13 towers with nearly 3000 residents, at Wolli Creek, just south of the Sydney CBD.

She said that maybe 20 owners could get an induction stove, but no more, thanks to electricity supply capacity constraints. EV charging faced similar challenges.

The “problem” with having enough electricity supply capacity is sometimes smaller than most “experts” and consultants think, especially in smaller apartments.

If electrification is combined with efficiency improvements, especially heat pumps, much less capacity is needed than most would think. The real world is very different from “expert perceptions”. Standards that include guidance on allowances for power requirements of lighting, appliances and equipment are outdated and don’t reflect efficiency improvements due to LED lighting and many appliances.

What’s the total 15 or 30 minute electricity demand for all tenancies and common areas?

First, it’s very important to get data from the local network provider about the total 15 or 30-minute electricity demand of all tenancies and common areas (with common area data separate from the rest).

I don’t think that has been done before, but it is critically important. If all tenants are lumped together, there should be no privacy issues. This data will tell us about the real demand from the diverse building population in 15 minute or half hourly detail, not the estimated demand.

Spinifex is an opinion column. If you would like to contribute, contact us to ask for a detailed brief.

With this data and some information about what types of equipment are being used for heating, hot water and cooking (often gas) and whether individual apartments have the equipment, or it is centrally supplied, as well as the number of apartments and likely occupancy, we can work out how and why present electricity consumption is occurring.

We can then work out what the likely demand would be if we applied various efficiency improvement options, demand management, solar and storage.

Peak demand will likely be dominated by heating and cooling, cooking and maybe hot water. A heat pump for heating can cut peak heating demand by 70 per cent relative to resistive heating such as fan heaters. Replacing resistive electric hot water with a heat pump will also cut that load by 70 per cent. For small households, heat pump HWS may use as little as 2 to 3 kilowatt-hours a day.

Induction cooking can have high peak demand but much lower for a diversified community

While electric induction cooking has high peak demand, it is for short periods, so, average peak demand is much lower for a diversified community than an individual appliance. Also, emerging induction cookers, such as those from the US, now have batteries, and some have power supply sockets for other kitchen appliances to reduce their peak demand dramatically.

Cooking doesn’t use much energy but has high spikes due to rapidly heating food and water. For example, an average electric cooking household uses 500-900 kilowatt-hours a year – only 1.5 -2.5 kWh a day – less than the standby losses from many electric hot water services or halogen lighting.

New induction cookers from the US have batteries, and some have power supply sockets for other kitchen appliances to reduce their peak demand dramatically.

Cooling loads can be cut by half with thermal upgrades

If an appropriately sized reverse cycle airconditioner replaces resistive electric heating, it reduces consumption by 70 per cent or more and has much lower peak demand. Thermal upgrades of the building will cut this by more. Gas heaters use some electricity for fans, pumps and controls.

I heat about 35 square metres (admittedly reasonably efficient) with a reverse cycle air conditioner that doesn’t use more than 700 watts in extreme weather – a plug in fan heater uses three times that and doesn’t heat as well. Most of the time, my unit uses much less.

Appropriately sized reverse cycle air conditioner replaces resistive electric heating; it reduces consumption by 70 per cent or more.

So, I suspect that careful analysis and selection of the emerging induction cooker technologies and heat pumps could allow many apartment buildings to use all electric sources within the present electricity supply capacity.

Also, if more was needed, a modest sized battery could smooth the peaks and use rooftop solar.

Many energy advisers have little idea of these opportunities when estimating demand. They tend to assume that inefficient electric equipment will remain or replace the present gas equipment.

My work with the Australian Alliance for Energy Productivity on several sites has shown that many energy consultants have little idea of these opportunities. They tend to assume that the present gas equipment will be replaced by inefficient electric equipment, and they ignore the potential of appliance upgrades and storage (electricity and heat and, in some cases, cooling). In many cases, old or faulty equipment uses a lot of electricity.

At Wolli Creek, the problems are different

In bigger apartment towers, such as in Carolin Wenzel’s article last week, you need network data for the whole apartment building to see the present electricity demand profile. Also, what are the existing technologies, not just the built-in stuff but also the plug-in stuff?

A lot of people have air fryers, electric kettles, microwaves, etcetera, that can have high peak demand for short periods but may be efficient overall.

While many induction cookers are rated at 10 kilowatts or more, most individual hotplates have short bursts to 2-3 kW but run at 200-800 watts steady state.

Many modern fridges run at under 1 kWh daily – 40 watts on average. A good reverse cycle air conditioner in a modestly sized room doesn’t use more than 700 watts flat out. Anyone whose apartment has halogen lights may use multiple kilowatts – LEDs might use 200 watts. So, the wiring of existing buildings is sized to accommodate much inefficient equipment.

Cars and charging

Charging EVs depends a lot on what you are trying to do. An average Australian car does about 35 kilometres a day. For a modern EV, that is about 5 kWh a day- a standard 10-amp power point can charge that in two to three hours. If people want more charging, they can go to a public charger. Smart chargers can manage overall EV charging demand and, in future, EVs will even be able to help supply building electricity demand.

Heat pumps are expensive

The point about the high capital cost of a large heat pump for central hot water is a challenge, and governments have ignored the importance of owner corporations, so most incentives don’t work for them.

There is a need for governments to tailor incentives to OCs. Also, many central gas hot water systems are appallingly inefficient due to poorly insulated ring mains, leaks, high standby losses etcetera. One 2016 report looked at a high rise apartment building in Sydney and one in Melbourne. For both, hot water was by far the biggest contributor to energy use. So, there is likely to be a lot of room for efficiency improvement in such systems.

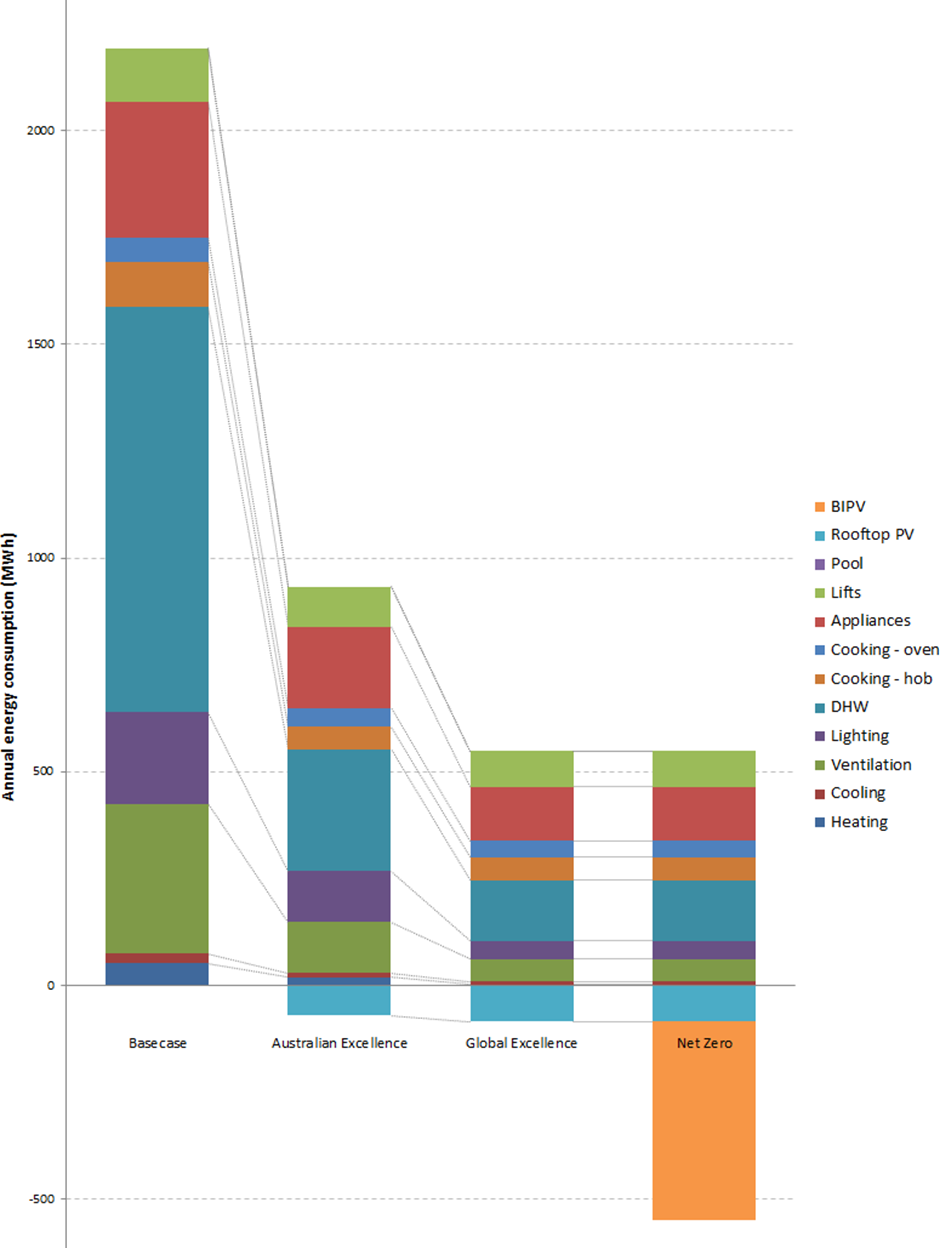

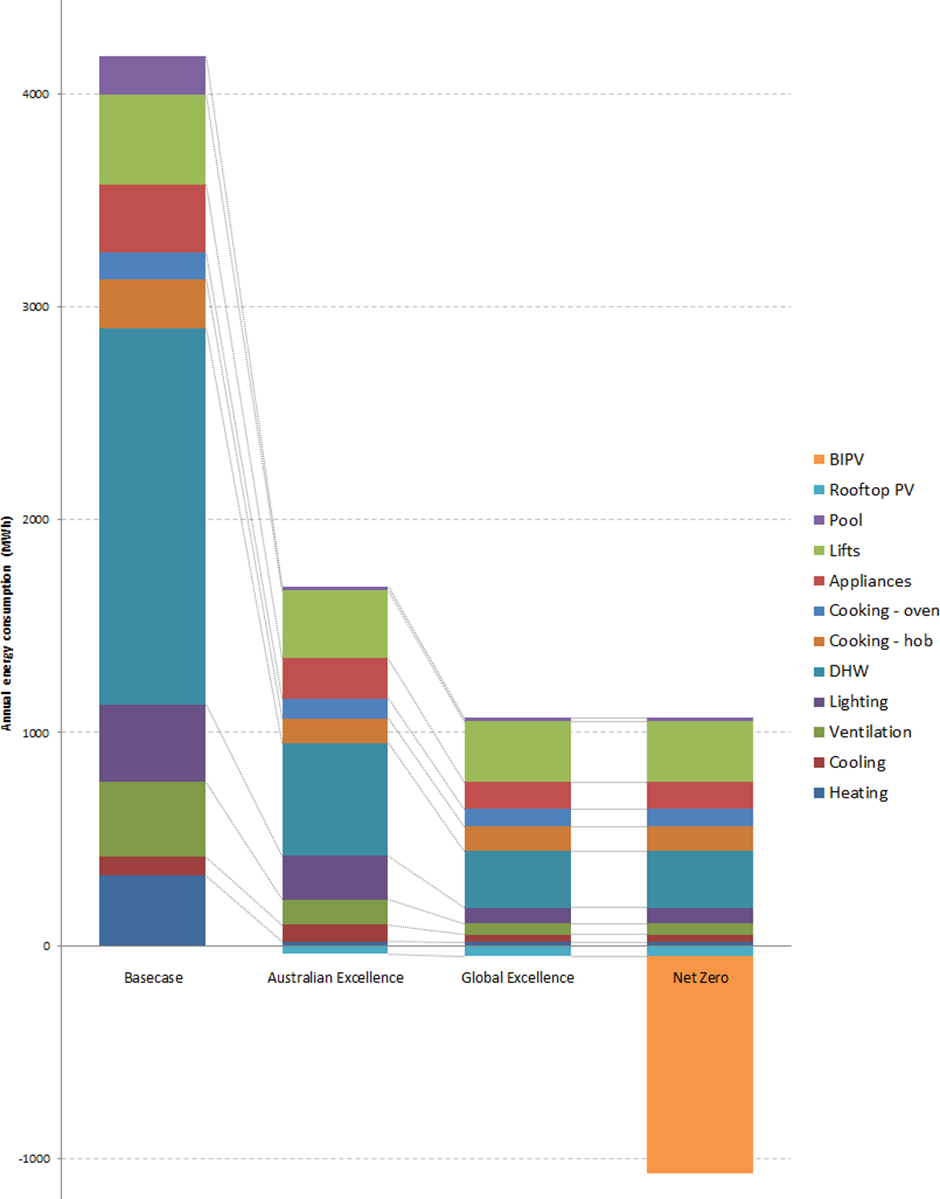

Source: Pitt & Sherry

There are now developments in induction cookers with smart batteries that can slash peak demand so they can run on a standard power point.

A heat pump dryer uses a third to half of the peak electricity of a standard dryer, uses a third to a quarter as much electricity overall, and dries more clothes… and doesn’t create condensation and mould, which drying clothes indoors on a clothes rack or in a conventional dryer does.

Certainly, upgrading building thermal efficiency is important for health as well as helping to electrify. So, while I agree there are many barriers for apartments (including the tenant-landlord split incentive [where the owner is expected to pay for the infrastructure but only the tenant benefits], and some of the options are still emerging, there is potential.

I use two portable inductions hotplates, an air fryer and a microwave for cooking, reverse cycle air conditioning for heating and cooling and a heat pump hot water service without an electrical upgrade – and my home was wired for gas appliances…

In the kitchen, I use a plug-in power board with a built-in circuit breaker, which has only been triggered a couple of times over several years. And since it is on the kitchen bench, I just switch one appliance off and reset it by pressing a button.

We shouldn’t let lack of information and outdated assumptions about how much appliances and lighting consume block efficient, flexible electrification of apartments.