Nearly a quarter of the way through the 21st century, Australia’s liberal, market-based democracy is looking increasingly fractured, and frequently ineffectual –precisely at the time we face great challenges, led by human-induced climate change. In this first of a three part series of articles, Murray Hogarth offers a thesis for how Australia has fallen into a state of energy and carbon policy dysfunction, just when we need the opposite.

Spinifex is an opinion column open to all our readers. We require 700+ words on issues related to sustainability especially in the built environment and in business. Contact us to submit your column or for a more detailed brief.

The drums are beating for election-time in Australia again, even if it’s still a year off. This time around, climate and energy policy will be a major and critical point of differentiation between the key parties and players.

I’ve been playing the last three decades or more back through my head – from an Australian perspective with global overtones.

Looking for the political or policy tipping point that landed us in our current state of climate action disarray, and policy dystopia.

I just keep coming back to the final years of the 1990s.

That’s when the Liberal Party of Australia – which should be rebranded the Conservative Party for truth in advertising reasons – began self-sacrificing its ideological soul, and intellectual coherence, by turning its back on carbon pricing and trading.

Above all, the Liberals are meant to be the pro-market party of government. Possessed by an unshakeable belief that private enterprise and free-as-possible markets do a better job of fulfilling people’s needs and wants than governments ever can.

As most serious economists agree, putting a price on carbon pollution has always been the most efficient and effective way to drive fossil fuels out, in a timely and orderly way. Thereby ushering in a clean-economy future circa mid-century. Before we cook the planet!

Of course, to embrace this wisdom, you have to accept climate science. Even as it keeps getting more and more dire.

You have to want to get rid of fossil fuels and replace them with zero emission alternatives – renewables, and in some countries nuclear, where it makes economic sense, which isn’t the case for Australia (latest CSIRO GenCost report) – as rapidly as possible.

If you do, then carbon pricing and trading can be the cross-economy, market-driven solution we’ve always needed, and the Liberals are meant to be the pro-market solution disciples.

Yet, the Liberals, at least at federal level, have been unanchored, and arguably unhinged when it comes to energy-carbon-climate policy, ever since they rejected carbon pricing, at odds with their own pro-market belief system. They are immersed in a series of intellectually-compromised culture wars, of which the dual wars on climate science and carbon action are by far the most consequential.

We will go back to look at how this unfolded between 1997 and 2014 in part 2 of this series and then how it is playing out in 2024 in part 3.

The climate crisis has moved from overly-optimistic scientific modelling to terrifying lived experience in Australia and globally. )For this I reference my friend and former colleague, Paul Gilding, including this recentsocial media post, with a potent warning about moving beyond “artificial hope”.)

But first, a bit more of my framing and context for this thesis.

In Australia, conservative politics governs mainly through the Coalition. It’s an often uneasy alliance between the Liberals and the National Party, which used to be the Country Party. (I grew up in the Queensland regions, in the socially-conservative Joh Bjelke-Petersen era, when the bush ruled the city at state-level thanks to a highly-effective electoral gerrymander.)

We can mainly exclude the Nationals from this analysis, however, because they’ve always been more opportunistic than ideological. They’re sometimes described as agrarian socialists, looking to socialise the costs and privatise the profits for their mainly rural and regional constituencies.

In today’s climate-change world, when the Nationals aren’t tilting at wind and solar farms, and high-voltage transmission lines, their constituency is getting out the government aid applications. For more frequent and severe floods when it rains. Longer and hotter droughts when it doesn’t. Then throw in some carbon credits for mainly pretending not to clear trees when it suits (my apology for this cynicism, and there are well-meaning “carbon farmers”, but inadequate voluntary carbon markets, in the absence of mandated ones, are part of the problem).

That said, the Nats are diminished too. At their worst they look like a Trumpian-lite bunch of rabble rousers doing the bidding of the mining and fossil fuel lobbies, puppet-like in bowing to powerful vested interests.

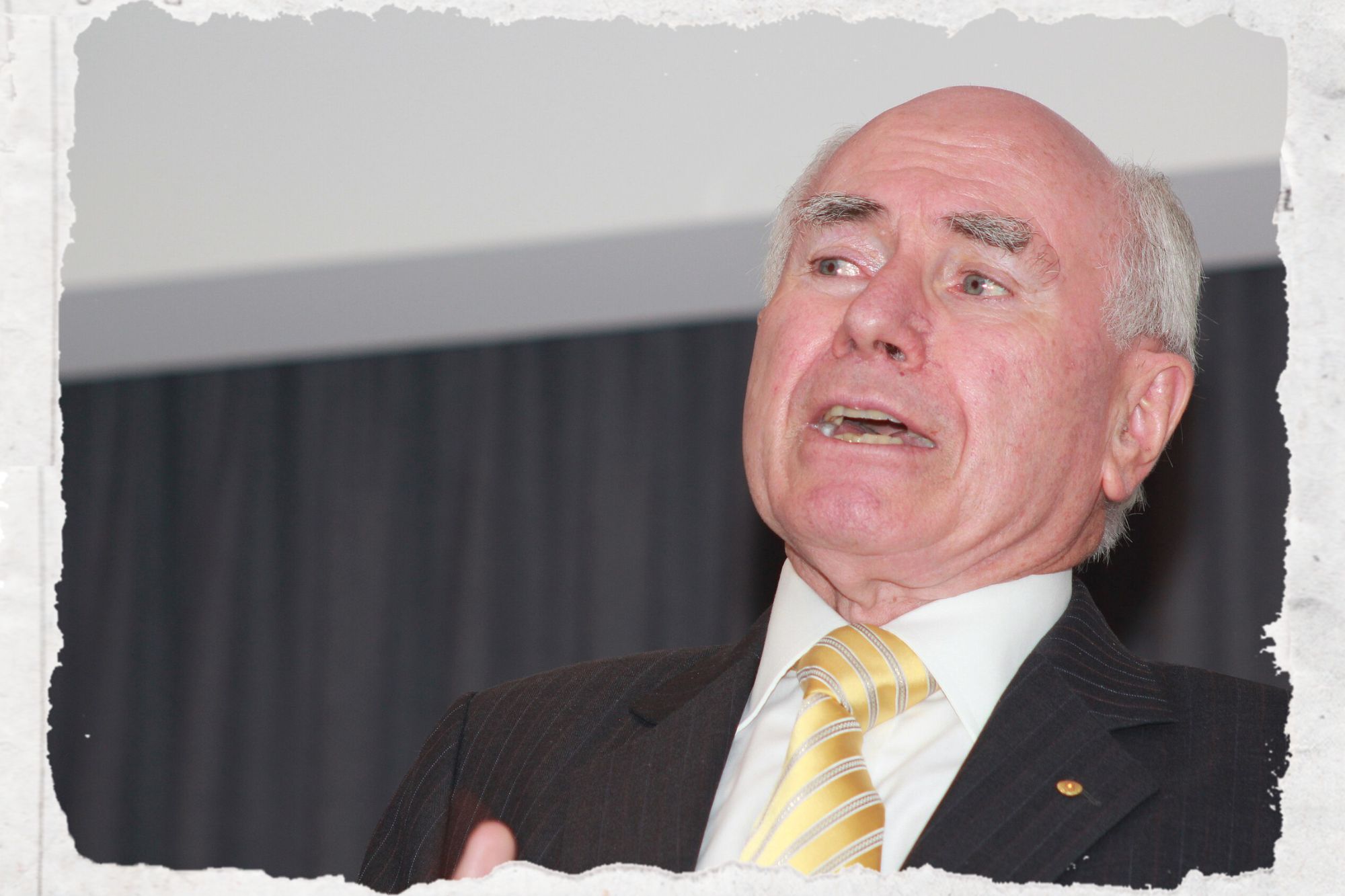

Even as a natural-born progressive, though never a party-political player, I look back fondly on the Liberal Prime Minister John Howard/Treasurer Peter Costello period of Coalition government running from 1996 until it ran out of electoral puff in 2007. Compared with what’s come since, it was a halcyon time for Australian conservative politics, including genuinely bold economic reform like the GST and the Future Fund.

Yet, this was also the period when the Liberals lost their way over carbon pricing. Then, over the following decade, they drifted into being dominated by climate denialism, and carbon and clean energy inaction,graduating now into fossil fuel nostalgia and nuclear power magical realism.

Somehow, we’ve all ended up in a kind of parallel universe, with politicised energy sources wrapped up in ideological contradictions.

In the dominant Liberals paradigm, it seems like free-from-the-environment wind and solar are left-wing, hydro may be neutral, and coal, gas, oil and nuclear reflect solid Right-wing values. Even if this props up democratically-disconsonant regimes like Saudi Arabia, favouring their oil well property rights and extortionate pricing over Australian energy self-reliance. The exact opposite of our strategic needs in a geo-politically fragile Oceania region!

It didn’t really start out this way, however, and it didn’t necessarily have to play out the way it has. But here we are, nonetheless.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/nov/06/climate-change-exaggerated-says-former-australian-pm

As a once wannabe Future Maker, I was under the delusion that John Howard did not accept climate change and his government worked hard at Kyoto to reduce Australia’s responsibility to pull our weight in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. I feel the Lib/Nat governments in Canberra have denied climate change in most of their policies since 1996.

Hi Carol, thank you for your comment. As I lived through it, including as a working journalist covering the environment round for the SMH (1997-1999), the Coalition leadership in the Howard-Costello era (1996-2007) were not climate deniers per se. And they took policy seriously, Although they certainly came to dig in on opposing the key policy measure available, a price on carbon. Howard came under greater public pressure on this circa 2006, and was giving ground headed into the 2007 election, indicating he would introduce a form of carbon trading if he won (he didn’t, that was the Kevin Rudd ‘climate election’, and a big win for Labor). Malcolm Turnbull, as Opposition Leader 2007-2009 continued to support carbon trading, but the Coalition slipped into climate denial and ever deeper opposition to carbon pricing and trading when Tony Abbott ousted Turnbull in a climate policy-driven Coalition leadership coup in 2009. Howard later appeared to renege on his earlier position (circa 2013, when his ideological mate Abbott became PM), becoming more supportive of the regressive Abbott position – and, in my view, less and less statesmanlike in his public position on the climate crisis.