The past practice of herding the impoverished into unloved enclaves and dark and dingy silos, often referred to as “suicide towers”, is rarely owned by governments. Subsequently, governments have never genuinely tried to reverse the stigma that automatically brands social housing hubs as criminogenic and the residents as undesirable.

This violation of dignity, which impairs life chances and undermines self-worth, has been burgeoning since the 1970s, fuelled by media hype, flawed public policy, real estate companies, and fragmented socioeconomic discourses. However, before this shift, public housing in the mid-1900s featured innovative and progressive design principles.

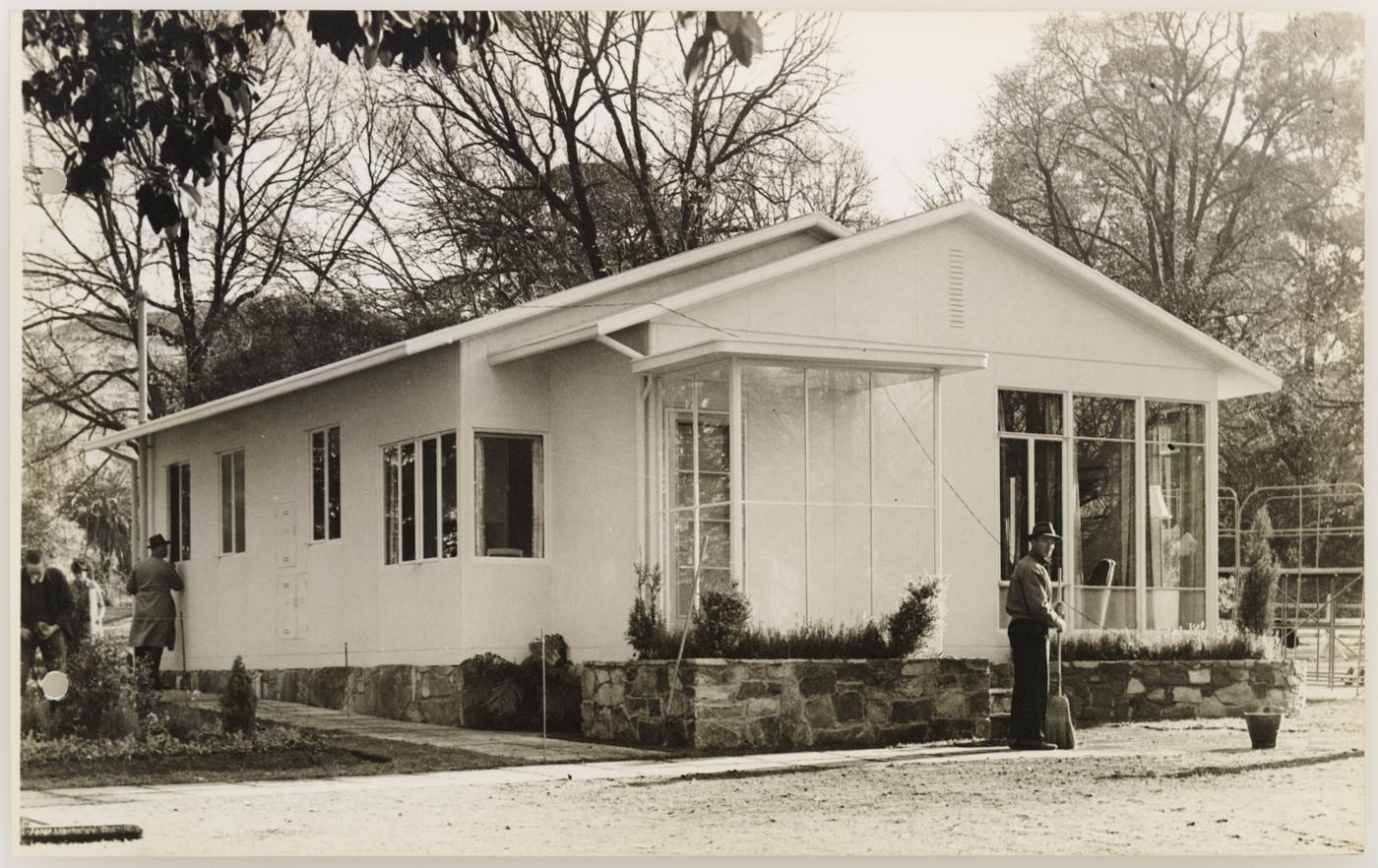

The Beaufort Homes, for example, designed by architect Arthur Baldwinson in collaboration with the Department of Aircraft Production and the Housing Commission Victoria in 1946, aimed to address the housing shortage in Australia post-World War II through a joint state and federal government initiative. New technology, factories, and a workforce developed during the war were repurposed for peacetime needs.

The Beaufort Homes were Australia’s first prefabricated steel homes. They were shipped in sections to sites around Victoria and the ACT for rental and private purchase. Designed as modular kits with a central core, they allowed for adding extra bedrooms. Research focused on creating ergonomic benchtops and “scientific kitchens” with efficient layouts.

Innovation gave way to market individualism

The rise of neoliberalism, debt reduction efforts, reform of the so called welfare state, and increased private homeownership in the mid to late 1990s reduced investment in social housing, resulting in its depletion and residualisation: public housing declined from 6 per cent of Australia’s housing stock in 1995-1996 to 2.9 per cent by 2019-2020.

In hindsight, with a little 1940s innovation and foresight into a pending housing crisis, the closure of Australia’s domestic car manufacturing factories from 2013 to 2017, which resulted in around 27,000 job losses, was an opportunity to repurpose those factories and redeploy the workers to manufacture Beaufort Homes mark 2.0.

Pinpointing when Australia lost its innovative edge is difficult, but it likely occurred during the 1990s when the government shifted innovation to the private sector and has been subsidising it ever since. We now have a risk-averse government committed to piecemeal progress and focused on gaining power or holding on to it.

Mending fences

The Australian government’s National Housing Accord is taking on the ambitious task of constructing “1.2 million new well?located homes” — inclusive of social and affordable homes — over five years from 2024 to 2025. It is an admirable and ambitious endeavour; however, scepticism surrounds the feasibility and efficacy of such a goal.

There are three main drivers of this scepticism: First, post the late 1990s, social housing has a history of poor design, poor quality, and neglect. We need to reverse all that. Second, “affordable housing” is a breezy misnomer and typically requires significant government subsidies. Third, governments at all levels have a poor record of achieving anything ambitious. That said, much worse is a government without ambition.

From this perspective, RMIT lecturer in housing and urban planning Liam Davies estimates that to restore social housing to 2011 levels, an additional 124,000 dwellings are needed in the next five years — 69,000 to address the shortfall and 55,000 to maintain levels at 4.6 per cent of housing stock.

In contrast, the federal government’s Housing Australia Future Fund aims to build 20,000 social homes and 10,000 affordable homes over five years, averaging 6,000 properties annually. This amount is only a quarter of Davies’ estimated requirement, meaning that while the program is ambitious, it still falls short of actual needs.

How much social housing is needed?

Calculating how much social housing is needed is challenging. As of June 2023, there were 446,000 social housing dwellings or around 4.1 per cent of Australia’s housing stock, with some experts suggesting 10 per cent is more appropriate. However, England, with around 17 per cent social housing, still faces an acute social housing shortage. Henceforth, mandating at least 10 percent of new housing developments as social housing will likely fall short.

On this, Prioritising is not one of our strong points. Judging what is efficacious and what should be rejected does not come easily. We often engage in nonsensical media hype and political imbroglios for months, years, and decades while other countries get on with the job. Watching a naive Ted O’Brien and a disingenuous Peter Dutton, in collaboration with Rupert Murdoch’s quislings at Sky News, flog a dead horse called nuclear power exemplifies this.

Who are the true architects of our discontent?

Besides our questionable judgment, while architects, designers, and developers face criticism for the social housing dilemma, local councils must bear the bulk of the blame. Although state and federal governments should adequately fund social and affordable housing, the onus is on local councils to streamline approval processes, develop facilitating land use policies and zoning, and create the neighbourhoods in which people want to live.

Moreover, architectural quality and aesthetics are important, but discussing social housing without referring to “amenity” — the liveability of a place —would be remiss. Amenity refers to the qualities that enhance the experience of residents and visitors, such as efficient public transport, well-maintained roads, bike and pedestrian paths, and effective drainage systems to prevent flooding.

Amenity also includes aesthetic features like leafy green trees that cool summer temperatures and resources like libraries and parks, which promote community interaction. In short, architectural quality and aesthetics combined with efficacious amenities are vital for eliminating postcode poverty and prejudice and, thus, creating stigma-free social housing.

Is stigma-free social housing even possible?

Architecture is critical in creating spaces that enhance psychological and physical wellbeing. With this in mind, the past serves as a cautionary tale, particularly with the decades of unsightly public housing designs that have failed to stand the test of time. Think of Kendall Tower in Redfern and Melbourne’s soon-to-be-repeated uncongenial public housing towers.

A plain façade, an unwelcome entrance, small windows, a paucity of light and detail, and unkempt gardens pervade a housing typology bereft of form, function, and architectural style. Towers, in particular, look more like office blocks stripped to the bare bones, both in terms of integrity and aesthetics.

The challenges of poverty and social dysfunction are deeply rooted in a suburb disenfranchised by an inculcated social housing stigma. This cycle of perception is self-perpetuating. The idea that “you’re lucky to have a roof over your head” cannot excuse poor architectural design and underserviced and unsuitable locations.

Social housing should be medium-density, compact, and adaptable to optimise space and promote community interaction. Ideally, it should be located near city centres for easy access to essential services, employment opportunities, and social hubs rather than on the outskirts of urban areas lacking inclusive infrastructure. Moreover, Indigenous social housing presents a unique challenge. It requires a culturally sensitive approach that reimagines our concept of Indigenous community design.

The neighbourhood NIMBYism imbroglio

In Australia, “objectively” assessing good or bad architectural design has been compromised for some time. Irrespective of the typology, housing is an emotional issue, with multifarious stakeholders and everyday Australians making emotionally charged judgments about what social housing should look like and where it should go.

However, the problem is not always in the design or the location but in the design process, which tends to prioritise the final product over innovative and inclusive approaches to getting there. Community projects often emphasise benefits like personal wellbeing, inclusiveness, and community connection, yet social housing is rarely included in these ideals and community discourses without some degree of public incredulity.

Regrettably, NIMBYism, or Not in My Backyard, often overshadows architectural quality and aesthetics as residents raise concerns about traffic, noise, crime, and declining property values. While some concerns are justified, NIMBYism can become a political football with very flexible rules, as advocates and opposers use it for both the approval and rejection of a new housing development.

Irrespective, however, a discussion about architectural quality and aesthetics is curiously absent and would likely be labelled elitist. Ironically, then, we are fated to complain that the architecture promised often feels incomplete as we seek more from it than just pragmatism and perfect proportions.

A little altruism can make us all feel better

Suffice it to say that social housing could use some altruism. Altruistic architecture is rich in meaning, encouraging personal reflection and interpretation from those who encounter it. In contrast, “political architecture” often acts as propaganda, delivering a singular message that limits engagement and exploration.

Altruistic architecture embodies the essence of individual experiences, transforming them into physical spaces and inviting others to connect with those places. In this way, the architecture intricately weaves a deeper connection to our sense of belonging in the world, enriching our understanding of ourselves and our relationship with our environment.

As Churchill said, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” It is imperative that the structures we create and inhabit are designed to nurture and uplift us rather than reinforce negative stereotypes and stigmas. Not perpetuating a stigma should be a priority.

Depoliticising the political power process

The foremost principle of social housing is to view it as a “system of physical and psychological renewal”. The primary objective should be to revitalise marginalised individuals as valuable community members while addressing the needs of both the natural and built environments.

Secondly, social housing must meet architectural standards equal to those of other housing typologies. Housing represents more than a human right; it is a vital endeavour that fosters belonging and deepens our understanding of ourselves and our communities, independent of anyone’s personal agenda.

Thirdly, urban planning is inherently political, shaped by political actors and affluent stakeholders. Research shows that state-led urban planning tends to favour the interests and ambitions of the political power elites. In short, irrespective of the planning strategy adopted, eliminating the stigmatisation of social housing requires depoliticising the political power dynamics in the planning process.

These are structural issues that sit outside current proposals and policies, highlighting the need for a radical rethink. Decades of privatisation and deregulation have led to inequality, homelessness, housing insecurity, and unaffordability. A system that prioritises profit over people’s wellbeing undermines the “core purpose of society”: to live happy, healthy, and fulfilling lives.

The question is: will we look back in 20 years and shudder at unsightly social housing disasters? Furthermore, what should social housing look like amid a climate and housing crisis? Naive endeavours to modify unsuitable locations prone to fire and flood will only deepen socioeconomic disparities and reinforce systemic postcode poverty and prejudice.